Final Fantasy IV: A Soundtrack Retrospective

ManaRedux’s note: You’ll notice that this post has nothing to do with Secret of Mana. A few years ago, I was asked to contribute to the apparently defunct Nintenhub project. Since I have a whole website for Secret of Mana, I figured I’d cover a different game for once. This was live on the site for about a year (published 2/26/22) before it went down.

It’s been over thirty years since we first heard the sounds of Final Fantasy IV for the Super Nintendo. As the second and third games in the series were not released outside of Japan, this was called Final Fantasy II for American gamers, one year after the release of the original.

Naturally, the acoustic offerings of the sequel were a more integral part of the experience. Gone were the 8-bit timbres with limited polyphony and range of the previous console. Now, something that sounded more like a saga was all around us. As designer Takashi Tokita noted, “Mr. Uematsu might have been thinking that if the graphics were going to be so much better the soundtrack had better match, so when composing I think he aimed for powerful, gallant music that sounds like an orchestra.”

Despite the improved hardware of the new console, there were still limitations. Voices were restricted to eight channels, some of which had to be reserved for sound effects. Production and memory constraints meant that tracks were often in AB (two-part) form—about one minute in length on average.

An often ignored facet were the systems that were reproducing the sound. Running a TV through an AV receiver was still uncommon at the time, and it was unlikely that players used headphones. Therefore, the sound was heard on TV speakers that were rarely designed for high fidelity. Despite this reality, composer Nobuo Uematsu’s music seldom became fatiguing, and most of the miniatures were highly memorable and functional elements of the game.

Final Fantasy IV features some of Uematsu’s most memorable melodies. Highly polished and dynamic thematic tracks were the manner of 16-bit era’s RPGs, and that’s exemplified here. The compositions sound like they’re for a specific purpose, and blatant experimentation and generic mood pieces aren’t to be found. The Overworld theme truly sounds like the story of a journey, filled with reflections of the changing landscape—from the grasslands and forests of the A section to the hills and mountains of the climax. This theme is reimplemented twice—in the underground, and the tragic Cry of Sorrow. This slow, stripped-down version shows the emotion of the main motif as a force in itself.

The town themes are also noteworthy. The generic track for these locations sounds like a return home, albeit one in pursuit of a goal. Toroia’s theme is appropriately more subdued—its simple harmony evokes the environment of the water town. The castle of Baron’s is appropriately majestic, while Fabul’s reveals the depth of a proud warrior culture.

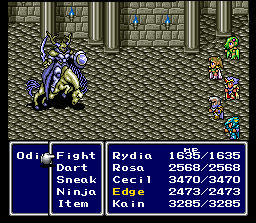

Perhaps the most striking pieces of the game are the boss battle themes. As with other types of scenes, Uematsu was able to compose different sounding tracks for similar purposes. The generic theme is an upbeat mysterious rock track with a high string line and a second section that reflects the latter parts of the battle. Dreadful Fight is the name of the track that plays for the four fiends of the elements, and it anticipates The Fierce Battle in Final Fantasy VI that served a similar purpose. Rarely did a video game track grab the attention of the player like this one, who didn’t hear it for the first time until the latter part of the first act. Its fast tempo is accentuated by a driving bass line throughout, as strings and brass alternate against vigorous percussion to tell the tale of these battles that come to take on a legendary tone.

The last battle of the game has a track that’s appropriately named The Final Battle. This combines elements of the previous two, with a dance feel and complex chords that reflect the conflict and its cosmic setting.

The centerpiece instrument of the soundtrack is a harp, evident from the first note of the game’s Prelude. Here, a single line with Classical inspirations and hall-like reverb eventually becomes the backing of a melody played by a small orchestra. The overworld theme is also started with inverted arpeggios on a harp that later keep time with the main theme. It’s no surprise that a player character, Edward, is a bard and harpist. His introspective talent actually becomes part of a battle in the midsection of the game. We can even imagine Edward as the harp musician throughout, playing with the orchestra off camera when not in the game. In addition to the harp, prominent horn choruses, emotive strings, and reeds are also featured in the soundtrack—the latter would extensively be used in Final Fantasy VI, the next American release of the series.

Perhaps the choice of these as the primary instruments makes Golbez’ theme so distinct. An ominous pipe organ buttressed by a choir signals the presence of the game’s villain. Other than Dancing Calbrena, the organ is not heard prominently for the rest of the game. It may seem formulaic but given the place and time it appears, it’s another of the game’s musical souvenirs.

Final Fantasy IV has been rereleased several times since the original and its tracks have been remixed for upgraded hardware and changing tastes. Also, many remixes and live performances of the game’s music have occurred, rearranged for different genres. One that was produced by Uematsu himself was Final Fantasy IV: Celtic Moon, an irish-themed interpretation of the soundtrack that was released around the same time as the game.

While its soundtrack was surpassed by its successor, there’s no doubt that Final Fantasy IV was an innovative exercise in what video game music was, and could become.

Launched some FFIV epic music on youtube while reading this.