Secret of Mana: a 30th Anniversary Retrospective

Secret of Mana: a 30th Anniversary Retrospective

October 15, 2023

It’s been 30 years.

And the images from that time are well preserved. My nine year old fingers trying to force a win over the Haunted Forest werewolves (it took dozens of tries), or Tropicallo (it took dozens more), or being surprised by two friends on a snow day who walked in just as I was finishing off Mech Rider #2 (and was quite proud of myself for needing only one try). We happened to have actual lemon candy like the round candy drops that day and also hot chocolate that wasn’t actually in Secret of Mana but somehow fit well.

Some years later, I was in college and chose failing out as my first major. Side effects of a failing out major include playing a lot of video games, and in my case it was time to revisit beloved titles from prior years. My personal canon includes the usual suspects from a decade prior: Final Fantasies, Mega Mans, Marios, Zeldas, Dragon Warriors, etc., but Secret of Mana had its own class.

By this, I don’t mean that the game was the greatest, but there was something about it that stood out. The whale sounds echoing through the wilderness were an invitation to explore an undefined mystery. The striking form of the Mana Fortress and the gloomy framework it was set against instilled a sense of dread and anticipation.

At some point, I’d likely have to go there.

Despite being designed for the obsolete Super Nintendo, there was a sense of vastness and sweep in the locales. This was accented by a uniquely dreamlike quality to the graphics and music.

There was also a sense that there was something, actually a lot more about Secret of Mana than could be found by playing it. Characters seemed to appear in the scenario and disappear almost immediately. Who was there had much promise, but little development. Entire dungeons seemed to end as soon as they began. Weight given to differing plot points was consistently unwieldy, and all of this seemed out of place in a Square game with such an enchanting concept.

Who could explain why so much was unexplained?

Even in the early 2000s, it didn’t take much time on the interwebs to learn that the translated SNES script I was playing represented a mere fraction of the original. There were also occasional rumors of a troubled development and large amounts of gameplay elements left unfinished. Eventually, an unusually large number of prerelease screenshots surfaced, at times showing what could have been a lost companion game. The prospect of experiencing more of this world became alluring. It became clear that in order to fully complete Secret of Mana, one was going to have to find out more than what they were given—something that wasn’t possible without taking an unprecedented journey through video game history.

I began to think…is this the Secret of Mana?

This exploration became an occasional pastime over the years and in 2016, I began to gather what I had discovered to that point, and created Secret of Mana: Redux to collect it in one place. In the ensuing years, myself and a cadre of like-minded Mana supporters have discovered more than early 2000s me could have fathomed. The near tragic outcome of an institution like Secret of Mana never getting its proper due stays with me to this day.

But despite all that’s transpired, I’ve never felt led to piece together the story from the beginning.

Until today.

A New Dawn for Mana

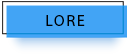

To see where it all began, we need to travel to the Akasaka district of Tokyo during the spring of 1991. Square Co. Ltd’s offices had moved there the previous year, and legendary video game offerings were being produced one after another. That spring, it was Final Fantasy IV and Seiken Densetsu (English: Legend of the Holy Sword, released in the US as Final Fantasy Adventure) that were nearing release. In the case of Final Fantasy IV, the long debugging phase was underway with just about everyone doubling up as a debugger regardless of their main role. The employees, with an average age of twenty-fourish, were given a build of the game to play ad infinitum, and a form to record any bugs that were found.

This meant many long nights at the office, with start times of 1PM not unheard of to accommodate the snoring army of debuggers. Even the break room was used as resting quarters.

Many new employees were given this work as their first task, and one of them was 19-year-old Shinichi Kameoka. Kameoka would go on to have a long career at both Square and his own business, but by this time he had only been a manga artist. His specialty was “hot-blooded” or “delinquent” manga (a theme often illustrated using an over-the-top theatrical aesthetic) that was in style then. With dreams of manga creation as a career, he felt compelled to work for an established company to learn a corporate system and write better manga in the future.

“I thought it might be good to experience getting a real job [just once] in order to gain enough common sense [about society]”, Kameoka would recall in 2012. “That’s the real reason I went job hunting…I casually applied for Square Co. Ltd. of that time. And quite casually I was hired by Square Co. Ltd. of that time.”

Kameoka was to share a single booth with four or five other new employees. It was dubbed “the cockpit”, and he quickly had his regimented lifestyle corrupted (or possibly enhanced) by the collegiate atmosphere at Square.

After a few months of debugging, work on Final Fantasy IV finally wrapped up. The game saw its Japanese release in July, and its US release as Final Fantasy II that November. As was the norm for Square employees needing to unwind, the veterans who worked on Final Fantasy IV left for a month in Hawaii. This left rookies like Kameoka to study the software and workstations for future games, while notably getting his own booth with a futon for the inevitable long nights making those future games.

“I still remember the joy of that moment!”, Kameoka said. “I could freely use the space of about thirty-five square feet surrounded by a partition. Whether putting up posters or lining up action figures, I could decorate the space as I pleased.”

Once everything had settled into place, a new era was dawning. Continued success meant more games could be made, and the development staff split into four divisions.

First was the Final Fantasy team led by Hironobu Sakaguchi. Their first task would be to make a simplified version of Final Fantasy IV called “Easy Type”, and then move onto Final Fantasy V. Next was Akitoshi Kawazu’s Romancing SaGa group, who were creating a SaGa title for the Super Famicom after the success of the recent Game Boy offerings. There was also Kazuhiko Aoki’s Simulation Team, seemingly researching production methods for future titles.

Twitter: mcclure111

Finally, there was the mysterious Maru Bird team (sometimes translated as “Maru Island.”). Led by veteran developer Hiromichi Tanaka, this special division was formed to produce Square’s first title for the upcoming Sony CD-ROM add-on to the Super Famicom. It would be created in collaboration with storied manga artist Akira Toriyama. “Maru Bird” was a clever way to obscure his involvement. In Japanese, it’s “marutori”—”Toriyama” means bird mountain, and “maru” is literally a circle.

Tanaka was one of the first employees hired at Square in 1983, and was instrumental in designing the Final Fantasy series. While not involved in the first Seiken Densetsu game, he was a logical choice to lead this groundbreaking venture.

“Chrono Trigger” was the codename for the planned title, coined due to the high anticipation of time travel elements and full utilization of the CD-ROM medium to depict vastly different eras and locations. Early on, Toriyama made frequent visits to Square, and artists like Kameoka took the initiative in studying his manga and recreating his characters as pixel art.

Sadly, complications soon emerged on the ambitious venture. First, Toriyama’s Dragon Ball serialization was extended another year, and he would not be available to collaborate until that commitment was fulfilled.

But most importantly, the CD-ROM add-on for the Super Famicom was in jeopardy as Sony became aware that Nintendo had been exploring a different scheme for a drive with Phillips, before production on the Chrono Trigger game began. As the CD-ROM drive’s release became doubtful (and eventually canceled), the Maru Bird team wanted to scrap what they had and start over with an entirely new production, but management asked them to scale down and rework the game to be released as another Super Famicom title.

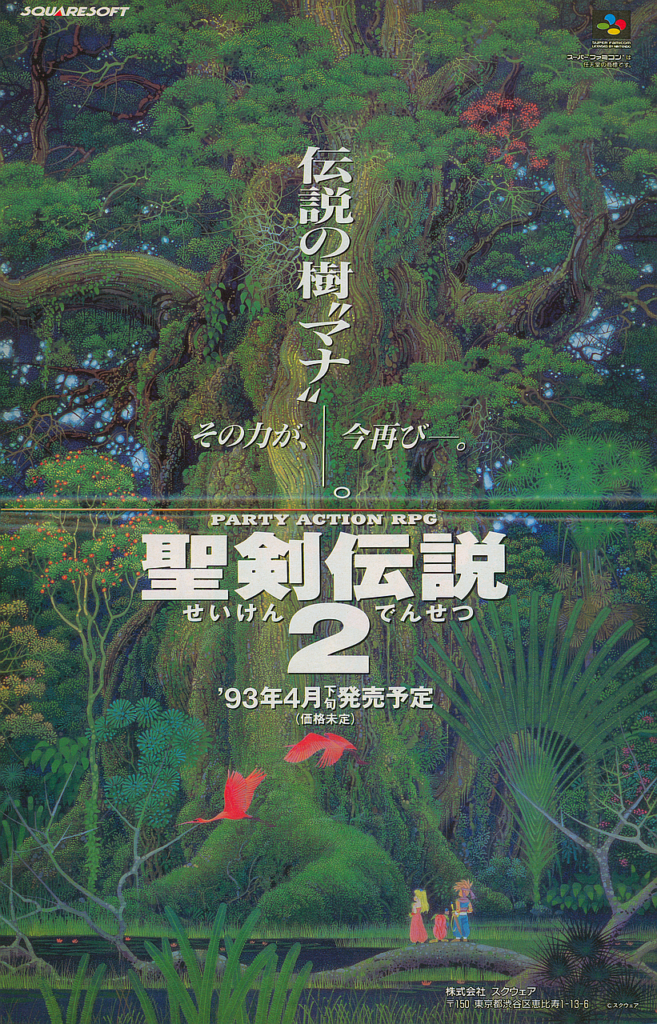

The resulting game would be produced as a sequel to Seiken Densetsu, appropriately named Seiken Densetsu 2. A separate Super Famicom game called Chrono Trigger was eventually released in 1995, also using material from the Maru Bird project, and it’s not clear how much of the planned CD game had itself been designed as a Seiken Densetsu sequel or something else entirely.

Ironically, the first Seiken Densetsu game also suffered a severe downgrade from original plans. Instead of a modest Game Boy offering, it was initially designed for the Famicom Disk System with the title Seiken Densetsu: The Emergence of Excalibur. Five individual disks were planned. Instead of hardware not materializing, it became the victim of nervous management who were not keen on such an ambitious project and its potentially steep price tag.

History tends to repeat, and the Maru Bird team began anew as the Seiken Densetsu 2 team. It was time to build off the success of the first title.

Honing the Legend

A new Seiken Densetsu game meant expanding the concept that was set forth in the first game, and looking for new avenues of inspiration.

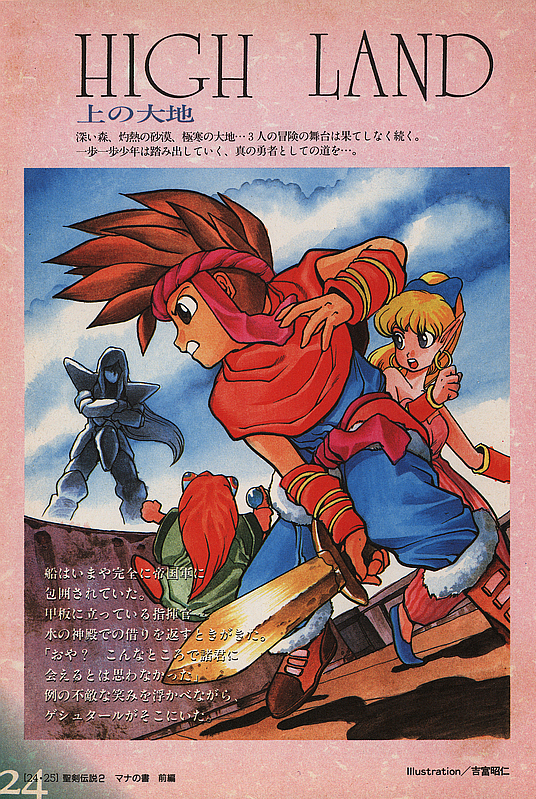

To create the series, designer Koichii Ishii drew inspiration from any source he could find to fulfill his dreams of a game that would have the same feel as a child’s storybook. To get this right, he watched scores of western animated films and looked at illustrations in western fairy tales. He also looked to his own childhood memories, even designing some enemies based on his boyhood nightmares.

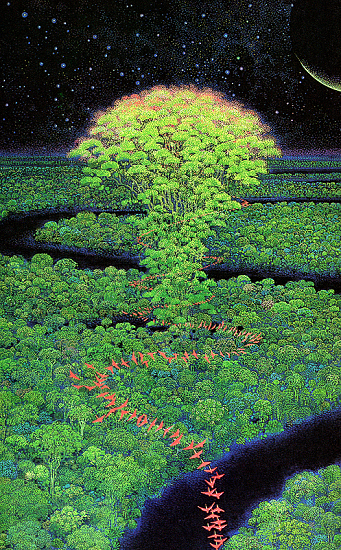

Ishii had joined Square in 1987 before creating the Seiken Densetsu series a few years later, leading production of the first title himself. Central to the Seiken Densetsu series is the concept of mana. “[It’s] the entity that unifies everything”, Ishii told Hippon Super! magazine in 1993. “Basically, it’s kind of like the source of everything existing, and it takes on a different shape depending on whether we’re talking about the planet, life, or individual people. In my mind, mana would be the entity that unifies everything.”

In the first game, the primary embodiment of mana was the gargantuan Mana Tree, a “world tree” that overlooked creation as a type of Gaia figure. “The Mana Tree is our interpretation of the cradle of life, it is where everything has arisen”, Ishii would later tell Level magazine in 2006. “A tree is a great fit as a metaphor for life, with its widespread branches representing different choices, or the clear division between the trunk, branches, and foliage which can be said to symbolize the various stages of life. Our fundamental idea was that we would create a world where everyone had the same origin and was a part of something bigger, and where everyone had something divine in them.”

But for Seiken Densetsu 2, there was a strong current in development to move away from the Mana Tree as a primary emphasis. Ishii continued, “…[In the first Seiken Densetsu game], we felt we placed too much focus on the Mana Tree itself, so for [the sequel], we’re emphasizing the way mana exists as an omnipresent energy force distributed throughout the entire universe. We wanted to depict the Mana Tree as an embodied representation of that power, but ultimately just one form of it.”

And the sequel had plenty of mana representatives. Most notable is the Mana Fortress, a stygian vessel with the godlike ability to absorb and redirect mana to fulfill humanity’s depravity and desire for conquest. A knight from the Mana Tribe used the Mana Sword to defeat the Fortress, later sealing it away with the power of eight Mana Seeds scattered throughout the world in Mana Temples. Each Seed represented a different element of magic—aiming for eight was an ambitious number as games to that point generally settled on four.

Of course, the concept of mana as a unifying lifeforce did not originate with the Seiken Densetsu series.

In a feature several months before the game’s release, Hippon Super! noted the concept of manna bread from the Book of Exodus, which YHWH provided to sustain the wandering Israelites following their escape from Egypt. But they added that while this is one possible origin of the word, the “mana” in Seiken Densetsu has quite a different meaning.

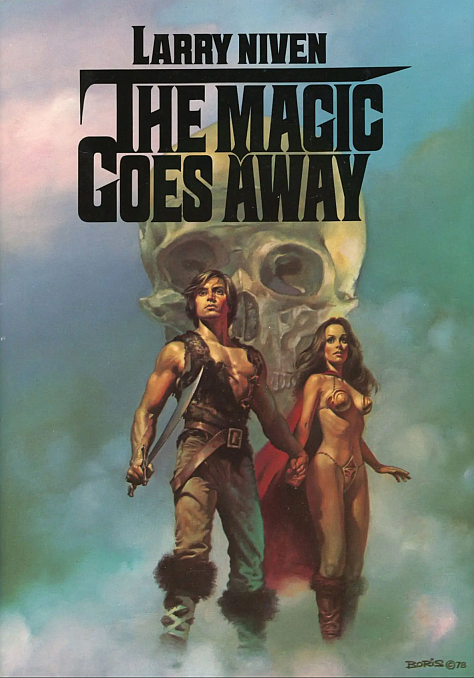

The same feature notes what may have been one of the developers’ primary inspirations for mana as an underlying force that sustains magic—Larry Niven’s 1976 short story The Magic Goes Away (released in Japan as The Magic Country is Disappearing). Here, mana is an energy necessary to use magic, and is specifically a limited substance. A postscript references the work of Mircea Eliade, who wrote much on the concept of mana in various world cultures:

“Of all the things that exist in the [realm of the] sublime, all without exception possess Mana. In fact, all that is seen by the eyes of man as effective, dynamic, creative, and perfect are like that [have Mana]. Historically, that general notion has had other names (orenda [Iroquois], wakan [Lakota], megbe [Mbuti], ugadi [??] ,etc.) in Oceania, North America, and Africa …”

In The Magic Goes Away, there’s a character known as the Warlock who anticipates Thanatos, the primary antagonist of Seiken Densetsu 2. The Warlock was a powerful sorcerer, many centuries old, who learned that if he stayed in one place too long, his powers decreased, and they would only return when he left that place. To compensate for this reality, he makes a contraption that gathers all of the mana in the surrounding area for his use, leading to a local failure in magic. Like Seiken Densetsu 2, this story features a powerful witch—this one was named Mirandee, who was formerly Warlock’s lover.

There was also some attention directed to the present state of the world. When asked what would happen to creation if the Mana Tree and the places and things where mana dwells were destroyed, the developers told Hippon Super!, “In many different meanings, the ‘balance’ [of mana] may be lost. For example, the destruction of nature and the environment occurring in our world today—what kind of effect might that have in the future?”

An endless array of influences are present in the gameplay. The developers again looked to the Wizardry series, which had been a strong early influence on Square’s developers. The Malikto spell from that series lent its name to the Malikto character in Seiken Densetsu 2 (localized as Mara in English). Seiken Densetsu 2’s treasure traps would also take their inspiration from that series, becoming one of its most memorable aspects.

Dungeons and Dragons was another one. While the names were changed for the US release, the Otyugh Ring and B-eye-lder Ring (corrupted for copyright reasons) items, as well as the Blood Roper, Otyugh Face, and Mega Zorn enemies came from the TSR game.

From the Space Battleship Yamato anime came the Wave Cannon and Diffuser Cannon weapons, and the Scorpion Army was more or less lifted directly from Time Bokan’s Doronbo Gang.

Star Wars references abound, as was typical of Square games of the era. There’s an enemy called Darth Matango (Mushgloom in English), a line in the Japanese script close to “May the power of mana be with you. Always”, and who can forget the evil empire whose massive apocalyptic vessel needs to be invaded and destroyed?

While in Akasaka, the staff spent many evenings at an Indian restaurant known as Moti, still in operation to this day. Moti would become the name of the dancing shopkeeper in the Seiken Densetsu series.

Finally, there was the neverending process of looking to other releases and reverse engineering them. As Kameoka would recall, “…team members also became enthusiastic to do better than the other teams…‘We will do better than the Final Fantasy team led by Mr. Sakaguchi!’, ambitiously thought by everyone who was not on the Final Fantasy team. Whenever a well-made game was released, we enjoyed analyzing it [in Square’s break room] with questions such as, ‘which is [the background graphics layer] and which is [the object layer]’?”

Creating the Secret

From the beginning, there was a desire to create an “action” RPG, in contrast to the menu or “command”-based RPGs that were in style at the time. This action RPG would stand out from the Zelda series, unlike the endless score of subpar Zelda clones that had flooded the Japanese market. This was problematic from a sales perspective, however. There was a sense that action RPGs would not sell better than menu RPGs, which were at their peak with the recent releases of Final Fantasy IV, SaGa 2 (Final Fantasy Legend II in the US), and Dragon Quest IV. The team compromised—they’d make a menu-based RPG that looked like an action one. This would have the added bonus of avoiding the need to develop skills like in pure action games like Street Fighter.

Hiromichi Tanaka spoke of the downsides of command-based RPGs, “[They] have treated combat as a different, separate ‘scene’ from the main game…We wanted to avoid that. We wanted to make a game that was simple and immediate to understand, on a sensory level, without being constrained by past forms or expectations about what an RPG should be…[We wanted to make sure that] what you imagined…on a battlefield matched what you saw on the screen.”

Koichi Ishii would add, “To give a more concrete example, take the side-view battles of Final Fantasy. Essentially, the experience is like a person at a zoo, standing behind the fence and throwing things at the animals in the cages. Then the elephant or whatever picks up an apple with its trunk and throws it back at you, and you take damage. In Seiken Densetsu 2, you fight in the cage with the animal.”

But they also didn’t want players to be able to make a fully powered attack with each press of a button like the Zelda series, so they designed a power bar that would start at zero and charge to 100% between each strike.

The sentiment for this direction long predated Seiken Densetsu 2. Tanaka was initially involved in Final Fantasy IV after working on the third title, hoping to add action RPG elements early in development. When it shaped up to be another command RPG, he decided to devote his energy elsewhere. However, it’s worth noting that Final Fantasy IV got part of the way there with its active time battle system. It stood in contrast to the older turn-based systems. Instead of the player’s set commands being executed in consecutive turns, the battle would feature continuous action with different player characters and enemies responding at different rates. When work on Seiken Densetsu 2 began, Koichi Ishii and lead programmer Nasir Gebelli studied Final Fantasy IV’s active time battle to gain inspiration for the upcoming action RPG.

The result was Seiken Densetsu 2’s “Motion Battle” system, which would become a large part of the eventual marketing hype. Nothing like this had been tried before—a hybrid command/action RPG where the player still managed resources and chose commands like the former, while traversing a continuously active battlefield and performing actions in “real time.” In reality, the system was not seamless—only three enemies can appear on the screen at a time. As soon as one enemy is defeated, another might take its place. This makes combat in Seiken Densetsu 2 a series of miniature battles that have the illusion of a nonstop process.

The Motion Battle system was the main reason that Tanaka felt that Seiken Densetsu 2, and not Final Fantasy IV, was the true sequel to Final Fantasy III. Many of the designs he would have used for an action-based Final Fantasy ended up being used in Seiken Densetsu 2.

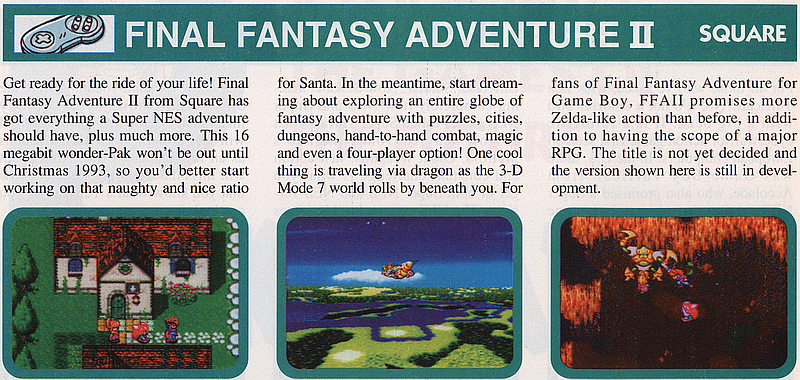

Initially, the player would only control one of the characters with the other two restricted to AI. When it was discovered how easy it would be to add a multiplayer option, the developers jumped at the opportunity, predicting that players would prefer human teammates over AI. This innovative decision turned out to be one of the most beloved aspects of Seiken Densetsu 2, turning it into a collaborative social experience. Even so, Seiken Densetu 2’s AI was robust for the era—one programmer was assigned the exclusive task of creating it for the entire course of development.

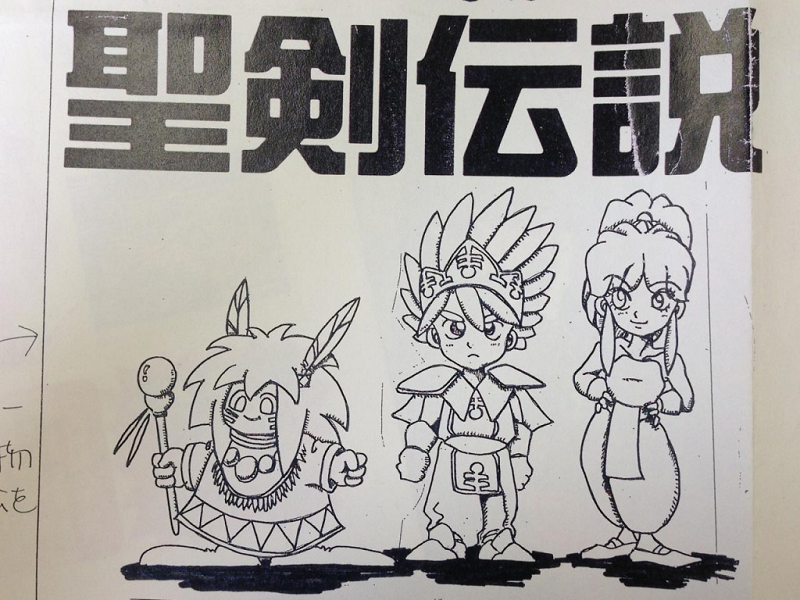

The prospect of four main characters was discarded in favor of three early in development, and designs by Shinichi Kameoka were chosen. Kameoka designed the boy and girl himself, while refining the design of the sprite from another artist.

Another iconic innovation was Flammie, the dragon-like creature whom the main characters travel the skies with late in the game. The name “Flammie” is localized from “Furami” in Japanese. This came from the name of a doll that belonged to a young lady who did English translations. Flammie was not in the original design documents, but the developers felt that a living creature could be better empathized with than a lifeless vessel like an airship. The most interesting animation idea proposed was the dragon, and in the setting design notes it was written how humans used creatures of Flammie’s species to ride the skies.

“We wanted something that felt more soft and floating”, Tanaka would recall. “Ideally something where you could close your eyes and imagine the feeling of the wind on your skin.”

The complex, graceful motions of Flammie raised fears that a custom chip would be needed to accommodate the animation, which would have raised the price of the game considerably. But Gebelli was credited with working magic that adapted his animation for the Super Famicom’s hardware. Gebelli also programmed the 3D-like perspective of riding Flammie, including the disappearing horizon line during travel.

Understandably, Flammie was one of the most hyped facets of Seiken Densetsu 2. A January 1993 Hippon Super! article said the following:

“The most overwhelming of the [prerelease] screenshots released are the Flammie flight scenes. It’s a so-called “vehicle” in terms of its role [in the game], and it will [naturally] appear in the game after the middle stage. But the beautiful thing is that it makes full use of the Super Famicom’s magnification/demagnification/rotation function, and it’s truly remarkable. You can freely look around 360°, move up and down, and change the viewing angle. If you remember Pilotwings, you understand the aura. Could this be enough for a whole game unto itself?”

Gebelli also invented the ring menu system, which eschewed the traditional design of menus in favor of a more active, dynamic design. Tanaka discussed this unusual way of selecting commands with Hippon Super!, acknowledging the gripes that some players had at first. “The good thing about the ring menus is that you don’t have to switch screens to access everything…When we were first designing it though, I had my doubts. It controls differently from your typical menu, and I thought it would be really cumbersome until players got used to it. Once you do though, it’s definitely quick and easy.”

The Sound of Mana

Video game music had come far by the time that development on Seiken Densetsu 2 was underway. The simple timbres of 8-bit systems had given way to the diverse sound library and more lifelike sound of the Super Famicom. This made sweeping soundtracks like Nobuo Uematsu’s recent work on Final Fantasy IV possible.

For Seiken Densetsu 2, Square turned to 29-year-old newcomer Hiroki Kikuta, whose arrival during this time mirrors that of Shinichi Kameoka. Kikuta had studied religion and anthropology at Kansai University before becoming a manga artist. Like Kameoka, he hoped to make a living doing this. Also a self-taught musician, Kikuta was open to music jobs too and avenues for composition work seemed to open up more readily.

One early job was a televised Snow White anime, which gave him the opportunity to write symphonic scores. His television composing experience eventually led to seeking work in the video game industry. His first choice was Falcom who rejected his application before he tried his luck with Square by sending a demo tape. He was immediately invited to interview despite never having touched one of Square’s games, or any RPG for that matter.

Showing up at the Akasaka office in a suit, he immediately hit it off with Uematsu (who had listened to his demo tape) with their shared love of progressive rock. Square would choose Kikuta out of dozens of other musicians. But once hired, he had the first task of debugging Final Fantasy IV.

“When the game froze up on me, I would raise my voice and say, ‘Um…there’s this bug here!’”, Kikuta would later recall. “That was how it started out.”

After work on Final Fantasy IV was finished, Kikuta was assigned to help Kenji Ito, composer for Romancing SaGa, with sound effects. There were many new hires, and this meant that there was sometimes a wait for new projects to become available. Square actually had a rule at the time that mandated one composer to one title, and Kikuta was to assist Ito until a new game needed a composer.

Kikuta described working on sound effects at Square at the time, “I was given absolutely no direction. If I created something interesting, they’d use it. Square basically functioned in that capacity. You did what you liked, and the best of what was created by the group was hand picked and combined together to make the end product. The company was almost more like a college club in its atmosphere, as if a group of hobbyists had taken over a corporation.”

In fact, Ito was intended to be the composer for Seiken Densetsu 2, but this was not realistic given his commitment to Romancing SaGa. Eventually, the project went to Kikuta, who was fated to join the “sleeping bag era” at Square, though he would have complete freedom with his work schedule to create what he had to. Kikuta practically lived at Square, and only went home twice per month during development.

“The magical atmosphere of the world of Seiken Densetsu had given me a wonderful inspiration in my heart, which also empowered me to produce good music”, he would recall to Destructoid in 2012.

Like the main development staff, Kikuta had to contend with the limitations of the Super Famicom. “The sound module in consumer hardware, represented by the SNES, was thought to be inferior and that good music could not be made using such a module”, he told Destructoid. “I was ambitious to show them that that was not the case, and that even if the module had lower performance capabilities, it could still generate beautiful music.”

Kikuta had to “fly blind” at first as image illustrators, scenario writers, and programmers were doing their earliest work while he was getting started himself. To get a sense of what might happen later, he struck up conversations around the office, and joined other team members for drinks after work.

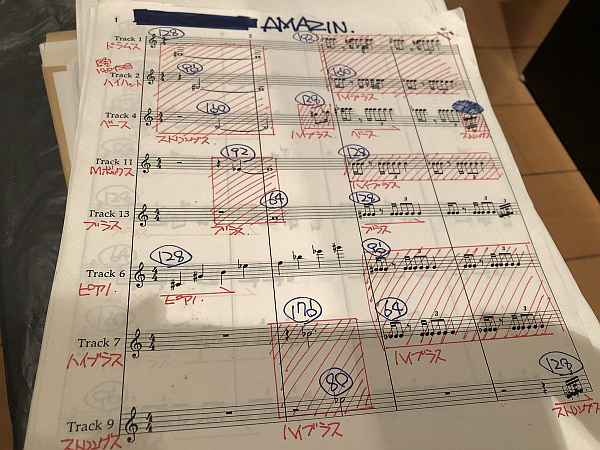

To save on memory, he experimented with rendering different instruments in varying quality levels without affecting the final result. He created sounds with his own synthesizer, and then planned how to map this work to the Super Famicom. This was the majority of Kikuta’s time working on Seiken Densetsu 2—composing the four dozen or so tunes seemed easier in retrospect.

“[Seiken Densetsu 2’s music] was limited by the Super Famicom hardware, but I wanted to emphasize a feeling of translucence and grandness. So I wrote that soundtrack in a very particular and special way. In my opinion, it came out perfectly”, Kikuta would tell J.S. Lawhead in 2019.

As for a favorite, Kikuta once said, “[If] I had to choose one song…I would have to choose ‘Danger.’ This track is packed with elements that best show what is characteristic of the music of Seiken Densetsu 2. It’s shocking, dramatic, and shakes up your emotions. Even among the fans, this is the song that they will recall first.”

Kikuta had inspirations from world music. In The Oracle track there’s the kecap monkey chant of Indonesia reimplemented in a heavy metal setting. The unsettling Ceremony track has similar influences with its use of the Indonesian pelog scale and gamelan arrangement. Dancing Animals get its rhythm from South Pacific Islander tribes.

In addition, his use of meditative and minimalist elements, irregular time signatures, and experimental timbres set the soundtrack for Seiken Densetsu 2 far apart from any of Square’s other offerings at the time.

The Trial Heats Up And Ends Fittingly

As development on Seiken Densetsu 2 progressed, Square’s staff was growing larger, approaching seventy early in 1992. This necessitated a move from Akasaka to Ebisu, where it soon ballooned to around 150, twenty of which were part of the Seiken Densetsu 2 development team.

The course of things was sluggish, with the team finding it difficult to overcome the limitations of the Seiken Densetsu 2’s hardware versus the anticipated CD-ROM drive they started with. This included the data space that was reduced from hundreds of potential megabytes to two. The console’s processor couldn’t keep up with the taxing Motion Battle system, and animation was routinely slow. Displayed images would flicker, and once again Gebelli’s ingenuity was called on to smooth things out. An April 1993 release date was pushed back to July, and later to August.

Other items like the title screen required some clever compromises. The displayed image is a highly compressed lossy algorithm JPEG, but still needs over a minute for the Super Famicom to decode it. So the reveal of the logo and opening text crawl helped stall for time while the image rendered and scrolled. Hiroki Kikuta composed the theme song after this was designed to accommodate the long reveal. Akira Ueda, the world map graphic designer, then improved this scene by animating the flamingos that were intended to be static. He cut out an illustration of a flamingo and divided it into parts, making a sixteen frame animation with wings flapping.

More compromises are evident in the final battle, where closeups of the Mana Beast only have three animation frames of its wings flapping up and down while its body remains perfectly still. This, and the distant Mana Beast depictions are coded as part of the background.

Too many tradeoffs occurred with the scenario to list, but it’s apparent that the first act was the most developed. The battlefield here is more refined than anywhere else in the game with many differences in terrain and opportunities for different tactics. The overhead view on Flammie recreates almost every detail on the ground.

Some dungeons were cut and pasted into others, like the Wind Temple that only exists as one room in the final. Cut rooms from the intended sequence were stitched together to make a pathway in the Underground Temple which would appear much earlier in the game.

In the final act, the Grand Temple and Lost Continent feel like a dumping ground for leftover characters to be resolved, and a place for many loose ends to be tied up at once.

It’s difficult to say how many of these reductions came from cartridge alterations, or simply not having the memory space or time to complete the intended work. The immense amount of external lore and setting information available in Japanese guides and manuals shows a huge world that only a small part of could be depicted in Seiken Densetsu 2. To this day, none of this has been officially translated into English.

The last stages of debugging finally commenced in March of 1993. Artists like Kameoka had to double as testers, seeing that their own work was implemented correctly. The team virtually lived at Square for three months until an almost bug free ROM was completed in June.

The mastering ceremony happened in the breakroom, early in the morning, as light meals were served with alcoholic beverages. Everyone took turns playing the game from the Mana Beast to the ending. But even at this juncture, trouble would hit, as Kameoka would recall twenty years later. “Alas, a bug occurred in the battle and the game froze. This troublesome bug was discovered at this inconvenient moment. Although we figured out the root cause, we knew it was going to take time to fix. So the staff who had been debugging all night ate the food, and the party was dismissed except the main staff.”

After the last found bug was fixed, the sales staff left with the master ROM on the Shinkansen train to Nintendo in Kyoto. Seiken Densetsu 2 would go on to be released on August 6th.

The American Release

The American release of Seiken Densetsu 2 would not occur until five months later, given the need for localization. The name “Secret of Mana” was famously chosen for this release.

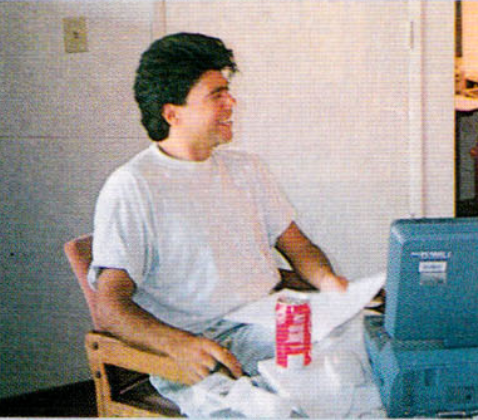

This assignment would go to prolific translator Ted Woolsey after his work on Final Fantasy Mystic Quest and Final Fantasy Legend III. Woolsey had earned an undergraduate degree in English at the University of Washington before completing a graduate degree in Japanese literature shortly before joining Square. He also lived for about five years in Japan on a glorified “culture trip.”

Woolsey was hired as a way to have an actual localization process, something that simply didn’t exist in earlier years. “They really didn’t have one”, Woolsey told Player One Podcast in 2007. “They had a person who spoke some English and she did her best…When I talked to the guys that hired me, the senior VP and the finance guy, they basically had spent some 24 hour blocks of time late into the evenings, trying to rewrite the screen text as best they could without ever having played the game.” It was Hironobu Sakaguchi that would seek to rectify this situation and Woolsey was hired. He had heard about Square after a college friend had translated a Game Boy manual for the firm, and suggested that he should pursue a job there.

Woolsey only had one month to translate the script, flying to Japan with his family in the final days of production in June of 1993. “I loved the look and feel of Secret of Mana the moment I saw the artwork for the game”, Woolsey said to Brendan McGrath in 2001. “I think the Secret of Mana team at Square in Japan did a phenomenal job putting together the adventure and story.” But the script was still being written, and sometimes things that had been translated the day before would have to be redone the next day.

Furthermore, as the lines in Seiken Densetu 2’s memory are not in chronological order, Woolsey had to play the entire Japanese game several times and make notes of the characters and storyline.

Woolsey’s finished work was sparse. When the first (known) full translation of Seiken Densetsu 2 was made by fans in 2020, the result was a script that was almost twice the size of Woolsey’s. It’s possible that he didn’t want to break up sentences across text blocks, but there was actually enough memory on the original cartridge for a much larger English script.

In addition to capturing only the essence of the original, his work receives criticism for errors and omissions throughout. Several plot elements in the Japanese text are left out, and many details are vague or plainly incorrect, especially in the case of minor characters.

But there are some fine moments in his script that go unnoticed. For instance, the Ninja’s Trump weapon in English is a great realization of the Japanese Fuma Shuriken. The Fuma were a ninja clan of Sengoku fame, and many weapons in other games were named after them. However, it’s also a likely reference to the Kamaiden manga, where a similarly named weapon was part of the ninja’s “hissatsu” repertoire, nicely captured by Ninja’s Trump.

There’s also the eternal line “But time flows like a river, and history repeats…” in the prologue, a paraphrase that is far apart from a literal translation of the Japanese text.

One must appreciate the constraints that Woolsey had to work in, and the fact that his result was still adequate for first generation English-speaking fans to experience the game. The original Japanese script is at times disappointing in its own lack of detail and explanations of story elements. Woolsey also had to contend with Nintendo’s strict content policy at the time, especially detrimental to a game like Secret of Mana with metaphysical themes. The relatively mild swearing and sexual innuendo had to be cut, but quasi-religious themes had to go too. Mana Temples became Mana Palaces, and there could be no mention of the Holy Sword that was the very namesake of Seiken Densetsu.

Time flows like a river…

Given the aspirations of the Maru Bird project, the Seiken Densetsu 2/Secret of Mana release was likely a disappointment. It didn’t get close to the sales figures of the Final Fantasy series, and would come in at #4 of Square’s best selling games for the Super Famicom/SNES. In fact, Seiken Densetsu 2 sold about as many copies in Japan as Romancing SaGa 2, and was dwarfed by the success of Final Fantasy V, developed concurrently.

In America, its popularity peaked in Nintendo Power’s Top 20 in April of 1994 at #6, remaining on the list until January of 1995. Here, it would sell about a third of what it had in Japan, but this was not unusual for RPGs at the time.

Secret of Mana has a small, but very loyal European following that was effected by its localizations there. A disproportionate number of fans come from Germany, the third most popular country for the game after Japan and the US. France and the UK also have notable Secret of Mana evangelists.

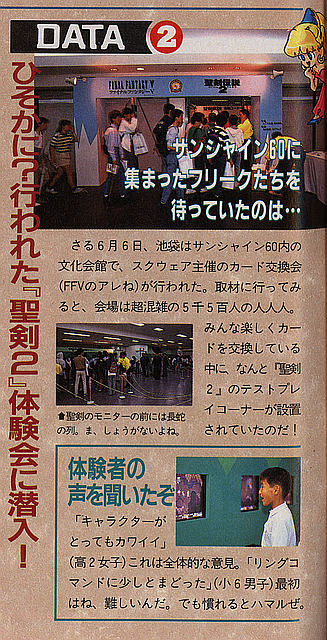

Source: Marukatsu Super Famicom, July 9, 1993

There was no rest for series production. With Seiken Densetsu 2 wrapped up, work immediately began on its successor. Seiken Densetsu 3 (later dubbed “Trials of Mana” for its western release) was first planned as a “direct continuation” according to Ishii, but the team ultimately decided to move on from Seiken Densetsu 2’s base and create a game in a different world without the Motion Battle system.

Seiken Densetsu 3 would have a 4 megabyte cartridge, double that of its predecessor, and the increased space allowed for developing graphics and animations further. The boss Dolan, whose large size and intricate form was not possible in Seiken Densetsu 2, was implemented in the new game.

The game that was finally released as Chrono Trigger in 1995 was developed at the same time. At last, Akira Toriyama could be involved, and he provided character illustrations and concept art for the new project. While Chrono Trigger kept the time-travel idea of the Maru Bird project alive, it was a very different game than Seiken Densetsu 2. The latter was a sequel to an established game, the former its own series. Furthermore, hardly anyone from the Seiken Densetsu 2 team worked on Chrono Trigger. It seems that while both games shared the same genesis, nothing significant in Chrono Trigger was intended to make an appearance in Seiken Densetsu 2. Hironobu Sakaguchi drove this point home, “[None] of our playtesters said that Chrono Trigger felt like Seiken Densetsu 2, and the Chrono Trigger developers didn’t have Seiken Densetsu 2 in mind when they were working.”

This makes us skeptical of the oft-recited tale where Chrono Trigger finished what Seiken Densetsu 2 couldn’t. Like the Seiken Densetsu 3 team, the Chrono Trigger team made full use of the 4 megabyte cartridge to replicate as many ideas from a CD-ROM based concept as they could.

Seiken Densetsu 2 itself was relatively neglected in terms of ports and remakes. A remake on Bandai’s WonderSwan Color was planned for release in 1999, but canceled due to the lack of market share of the console. This fate was shared by canceled remakes of Final Fantasy III and Romancing SaGa. Both of these releases would have included significant new content and upgrades to the original ROMs, and it’s possible that Seiken Densetsu 2 would have received a similar treatment. There’s virtually no information on how far the project came along before being canceled. Some years later, another remake was planned in the style of Sword of Mana, but other than a few screenshots, little is known about this too.

Only a mobile phone version was made in the first quarter century after the game’s release. A disappointing 3D remake with voice acting went on sale in 2018, with hardly any of the charm of the original or what made it so memorable. Among the letdowns are the lack of Cannon Travel animation due to technical problems, and an uninspiring script that is heavily derivative of Woolsey’s and left much of the original unavailable for English-speaking players. Finally, the characters would make their first “new” appearance in the 2022 Echoes of Mana gacha game.

~

Today, the game remains a nostalgic institution, far greater than the sum of its parts as time will surely reveal more of its mysteries. Secret of Mana is what it is, and for that we should be eternally grateful.

Always thankful to: Queue, Taosenai, Hiro Amano, Yoshi Fukagawa, BahamutArk, Michele di Fronzo

Sources: Dengeki interview with Hiromichi Tanaka and Koichi Ishii, 1992; Hippon Super! Magazine, various articles and interviews, 1993; V Jump, 1993; Play Magazine interview with Ted Woolsey, 1994; Famicom Tsuushin, Dengeki Super Famicom, and Haou Magazines, various interviews, 1995; Brendan McGrath’s interview with Ted Woolsey, 2001; Dengeki interview with Hiromichi Tanaka and Tomoya Asano, 2006; Truth About Mana, Level Magazine interview with Hiromichi Tanaka and Koichii Ishii, 2006; Player One Podcast interview with Ted Woolsey, 2007; Square Haven interview with Hiroki Kikuta, 2007; Square Enix Music Interview with Hiroki Kikuta, 2009; The Secrets of Mana, Retro Gamer, 2011; Destructoid Interview with Hiroki Kikuta, 2012; The Story of Those Days, 2012-2013 [from Shinichi Kameoka’s blog]; Undead Labs Developer Bio: Ted Woolsey, 2016; Game Watch Interview with Shinichi Kameoka and Koji Tsuda, 2018; Official Setting Material + Complete Strategy Guide, 2018 [Remake]; J.S. Lawhead’s Interview with Hiroki Kikuta, 2019; Secret of Mana: Reborn Commentary [Fan Translation], 2020, SNES-CD Prototype Image By Nintendo/Sony – Original publication: Circa 1991 http://www.ugo.com/games/snes-cd, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37048874